Interview

Excerpted synopsis of an interview conducted

by Bernard Chevassu (as transcribed in first-

person format by him) February 26, 1989 in

Nyon, Switzerland (translated by Louis Pelosi)

I arrived in Switzerland in !959 as a maid in families, waiting for my orphan’s

pension from Germany. But what I did at that time myself since the age of

twelve is tapestry. I loved the crossing of fibers, the crossing that you find

again in the drawings besides, crossing of the horizontal and the vertical. At that

time though, I didn’t know anything special for myself.

And that passion came by itself. And my husband discovered last year at a

relative’s home in Bonn my first tapestry done at twelve. And you find there

already similarities at the level of strokes and movements. I discovered that

I had done birds in flight, and in fact I had done humans in flight, a lot, and

the flight part could be found already in my tapestry. It was my own world

that allowed me to isolate myself, and I adored that isolation. I love isolation

because it favors things I can’t bring out in the company of people. But I

could isolate myself in the framework of the orphanage. In effect, since there

were a lot of kids, they didn’t count if one was absent, and that was my way

to escape. It was part of my day, isolation.

And the creation of my tapestry was a need like drinking and eating, part of

my daily life. And I came through emptied out, but emptied to start something

else. And I loved tapestry very much, because it took a very long time; I loved

that duration that isn’t there in drawing, with the brush, because you must

discharge an emotion very quickly. But that emotion must build up first two,

three years, in order that I might give to the brush what will be accomplished

in maybe a minute, in a second … And afterwards I don’t do brush drawings

anymore for several years. With the rapidograph it’s very different. Maybe I do

drawing for three or four days, for a notebook of sixty pages, but filling in the

ground takes me on the other hand six or seven months. So again it’s the

vertical in the horizontal, peopling the surface with the cross-hatching. And my

tapestries were huge … and that required a labor of eighteen months to two

and a half years for a single tapestry.

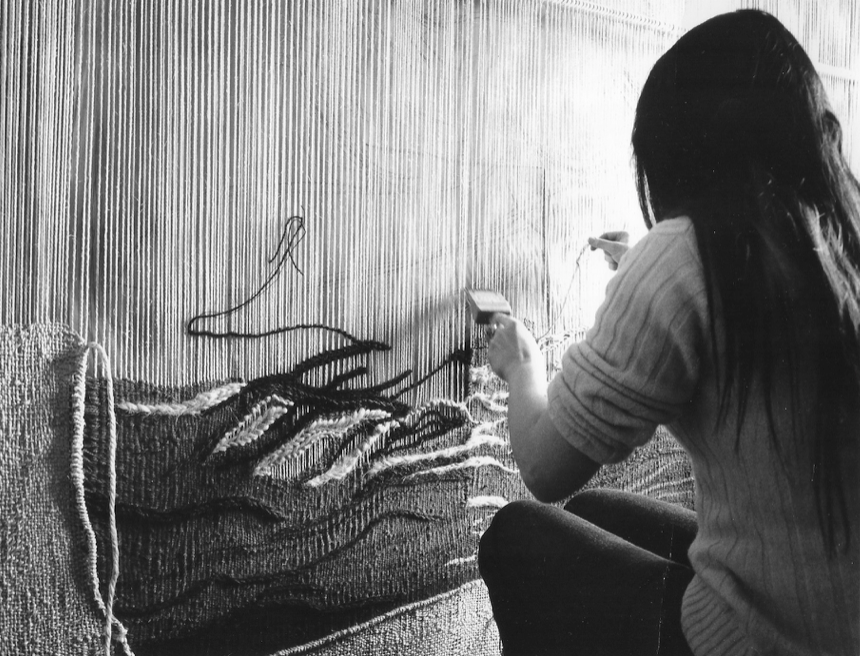

Photo by Jean-Marc Fontaine 1976

The important thing for me was to have done them, and the fact of having made

them already attracted people to them. I tried myself to show them, and I was

pleased to show them. The first time, I set myself to work for five years and

after that to show my work in an exhibition. I wanted to share the pleasure of

color, the pleasure of discovery of what I called the “silent world,” because the

mineral or vegetal world cannot be expressed in words. I could only do it with

materials, and that I could share. And the colors I used were quite vivid — red,

orange, yellow, green all put together. Some saw this as aggressive because I

notice that in Switzerland the colors are generally dark or earthy, and I disturbed

the people with my colors.

In effect I have often seen that in front of my tapestries people were put off by

the colors, they didn’t like them whereas for me it was a joie de vivre. And then I

didn’t just work on the surface, but with the volume as well, the … relief, even if

I don’t do that anymore. Besides I invented a loom that allowed me to work

behind and in front. So you could see behind and in front, and I liked that

invention, because it permitted me to create spaces you could see from each side.

That tapestry could be hung, suspended, placed in the round …

Photo by Francois Martin, Geneva ca. 1971

In Geneva I even found doors of old houses being demolished; I brought one

back, took out the inside and carried it into the middle of a room, then

constructed a tapestry tower around it. Then I removed the door which had

played the role of a scaffold for my tapestry. That’s how I could make entirely

different kinds of tapestries, which wasn’t possible with a standard loom.

ca. 1970

It was at the same time a textile sculpture and an Indian hut. These were

“Ubuesque” tapestries. That’s what they were called when I presented them.

And for the materials I used only raw materials like sisal or hemp or jute, coco …

Crude or rough materials that I mixed with silk, wool, goat hair, horsetail hairs

used for a bow that a violinist gave me. I myself straightened them because

they had glue on them. I trimmed all that out in a bath then washed it in soap.

And when it was undone, I rinsed everything in vinegar and that’s how I made

use of it for my tapestry … And I learned these techniques through my reading.

I had a terrible thirst to learn everything that had to do with primitive art. So

I immersed myself in the ethnographic libraries of Basel or Geneva. I borrowed

books from the Geneva library, copied the primitive techniques and tried them

in tapestry … I adored that.

completed Tour (Tower) 9’ x 6.25’ x 6.25’ ca.1971 Collection de l’Art Brut

And that’s how I found the very old, very special techniques. For example I

discovered a book called Knots of the Hands. It’s a book with nearly 8000 notes

on the manner of fashioning knots, and I used it for tapestry …

And then I passed into art school for, not having made any studies at all apart

from the courses at the orphanage, I wanted to know everything on the history of

painting, the history of its techniques. For that I needed to learn how the masters

had worked. But what I would have preferred is to have studied in the studio of

a master than at a school.

And to get into the Ecole des Arts Decoratifs in Geneva I prepared a dossier that

I worked on evenings, and then at the school I learned classical tapestry … I

researched how everything worked. So I unrolled all that I had just done to know

how it worked. And I asked lots of questions and the people didn’t understand

why I was disturbing the whole system. It put everything in question, their

whole equilibrium even though it was not my intention to upset them. My mind

was such that I would not admit that anything was definitive. I had to take

everything apart to do something different. And in painting I did the same.

Same with the recipes I was given, I didn’t apply them at all, I tried out myself

what that gave.

Alongside tapestry I worked at painting as well, drawing, set design, engraving,

lithography, etching on copper, textile painting …

But at that time I wasn’t showing, except for participating in a painting exhibition

my first year in art school, where I attempted painting with sand … But my

tapestry work had not been shown at all, not because I didn’t want to, but because

that wasn’t done in the French part of Switzerland. And then you saw few artists

preparing a show on tapestry, because that takes many years and generally you

work on tapestry by commission. You could hardly invest five years in something

one doesn’t know what to do with. Me, I said, “No!” I want to do tapestry, which

pleases me, show that which I am pleased with. I was sure that would please

others as well if they saw a real consistency. And my grandfather always told me,

“If you persevere in something, a person will always recompense another.” And

I still believe in this principle. And the people who saw my first works found

them fantastic, even if the colors were a bit aggressive. And then I began to know

lots of human warmth …

Thus my first showing goes back to 1961 I think, for painting anyway, and 1966

for tapestry. As for my first solo show, that goes back to 1970. And in 1979 I did

an entire exhibition on the Symphony No. 3 of Mahler, and I worked five years

relentlessly on that show. And if I worked on the side, it was to be self-sufficient …

work in progress 1976

And what I did on the weekends … was my drawings. I had an eight-power

magnifying glass, and on all fours I would study on the ground all nature, and I

did sketchbooks of drawings. And I noticed that some things transformed into

people, like tree branches or vine stocks. Everything was changing into humans,

and little by little I started to make human figures in tapestry. I was seeing in

Foret de Mains (Forest of Hands) ca. 1979

them faces in movement … entire heads with arms in silk or in coco, in three

dimensions, and I would position together a head, an arm, on the floor. I also

brought together several figures, or I would embroider on them, but all that

didn’t satisfy me.

And one day I found myself in front of a store. I bought rapidographs and that’s

how I started with my drawings. And it was all done with ink. And afterwards I

worked the people a lot, but not from the outside, with contours as one does with

tapestry; everything was filled. And since at art school we studied anatomy, we

still went to the medical institute to look for arms, and we opened them and we

drew them. So I know the human figure in all its positions. That helps me a lot

now, and even if it’s been twenty years since I left the academy on the side, I

know how to distort figures; I can imagine … At the academy I didn’t like drawing,

I detested it even, but I saw it was necessary in order for me to forget. So I keep

only the essence of the person. In any case all human beings have birth, death

and sickness in common, and I go right to the essential because I know what’s

awaiting us. Between birth and death we fill up our passage, and even if each day

is a miracle of life, if each morning when I wake up I say to myself that it’s

exceptional whoever we encounter, although all the others are of course

preoccupied with themselves, it’s nonetheless extraordinary that we might still

give something other than anguish over death. The fantastic thing is enthusiasm

for life, the fact that every day is a victory over death. What is not normal is to

consider as normal the simplest things, like walking, whereas all that is

extraordinary. So it is that for me each day is a kind of wonderment. And the

more I advance from “the other side,” the more I find that I have still so much

to do, maybe because earlier I didn’t have that sensibility for things, while now

there’s a contact, a constant surprise. Everything, even a tiny detail, is a source

of wonder.

And in my drawings I think you recognize that in the movement, in that intensity

of movement. But you discover as well that we go to a final point. There is a

sort of conflict between the two, a kind of permanent debate. And all this happens

in a cyclical way.

Drawing (detail) 1983 Artist’s estate

Besides I always work this way. There are seasons, moments when I work with

more intensity than others. I feel the passage from one season to another very

strongly, but the most propitious times for creation are spring and winter because

we live inside … I love when I’m given the chance to isolate myself, when

everything is cold and I’m indoors. I live in a natural surroundings that lends

itself to that. I don’t like city life, I’m terribly afraid of the city, of the

uncontrollable, chaotic activity that characterizes it. And then there’s the fact

of running into so many people all going to the same end, but what they do I

don’t know and it troubles me. Emotionally I can’t handle it.

And the ones I represent are individuals I meet on the street who at times, just

by their look, affect me terribly without their even having spoken. I can’t forget

them; it’s a visual memory. The way poets fashion words, I fashion the human

figure. Not flowers, not trees, only the human because he is the only animal who

knows he is going to die … What I remember are the faces, the hands, the gaze,

the expressions, full of the details of the life I wouldn’t have been able to express

at twenty … The man/woman aspect doesn’t exist. Quite simply it’s a human

being, and what interests me is his or her motivation … And when there are so

many of them, like in New York, with so many different motivations, I can’t

handle it. I can’t take it all in, it’s too much. And this perception of others’

tensions is moreover so strong that it makes me ill, really ill. When I go into

town, I come back totally exhausted. Like a medium, I feel that others are letting

out their aggressiveness on me, and I discharge it elsewhere …

Drawing (detail) 1985 Artist’s estate

Drawing can be enough to discharge all that is in oneself, it’s strong enough for

that. But, being something quite slow, when an emotion is sensed, I need time,

and when I perceive an aggression, that takes time to reverberate after the blow.

It might come out weeks or years afterwards …

My essential work, I think, is drawing, and when I represent a figure, I need to

repeat it in painting. I can’t leave it on the side until it be exorcized. Thus I have

done a man standing up holding in his hands something he was protecting

fifteen times, a man on his knees seven times. But when this figure is finished,

I don’t touch it anymore.

Standing Man series in progress 1984 (later retitled Homage to Stacho) 8’ x 6’ Collection de Stadshof (finished work on loan to the QCC Art Gallery)

There wasn’t a direct passage from tapestry to painting. There was drawing,

that of nature — leaves, grasses, minerals, shells flowers, branchings, each

thing for itself like a species of dictionary. And it was no longer tree branches,

vine stocks, plane trees — and then it became men, and that’s how it all became

clearer …